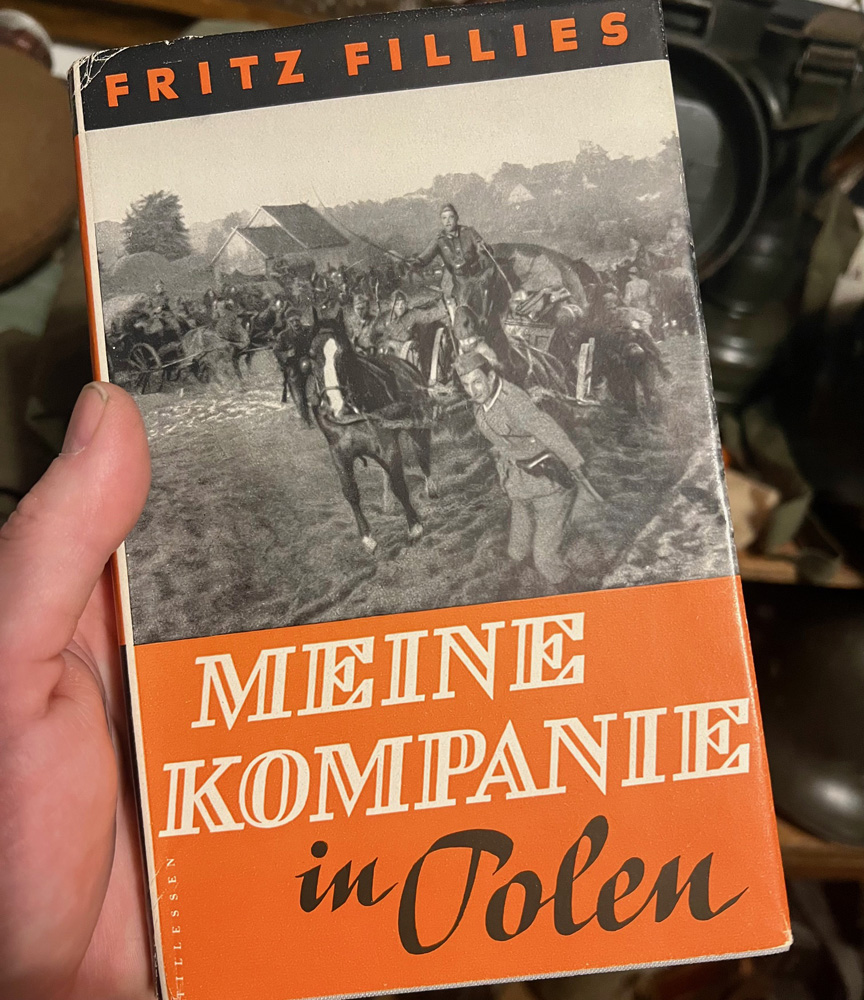

“Meine Kompanie in Polen” (My Company in Poland) by Fritz Fillies was published in 1940. Fillies had been an Oberleutnant and Kompanie commander in the Polish campaign, and the book was his memoir and recounting of the events of September 1939. The forward to the book was a story about the days after the victory, and a Polish typewriter on which the book was written.

Polish Typewriter

“These lines owe their lives to a Polish typewriter, on which they were written. A few days ago, Warsaw, in front of which we were recently deployed, has fallen. We lie in a small Polish village named Szlachecka, half way between Pultusk and Ortelsburg and in the middle of the flat landscape, with its sparse coniferous forests and sandy fields, its poor villages and even poorer farmers, that we came to know on the advance in September. Our Infantry Regiment took part in the watch on the East Prussian border, the advance and pursuit, the combing out of the forests and the siege of Praga. There, on the second to last day, we had seven dead, and sixteen wounded. Since then, we marched here, to the villages, leaving the war behind, and awaiting the things that will come there. When it happens, the order might be: To the Rhine – or: In the garrison. We don’t know, and we wait.

In the meantime, we get ourselves and the things that belong to us back in order. Now it is time to shave and to wash again, to care for the horses, to get the guns and tractors, which have been maintained by the boys to the best of their abilities, inspection ready again, and to write letters home, not just postcards. Now is time and rest for everything. These days seem like a gift, they are so unbelievably regular, serene and beautiful. How bizarre such a war is! There is even leisure, real leisure. The war is so diverse in its forms of expression, it is as if it says with a friendly gesture: Stand back! Now step away from me!

And that, we do. We do everything it wants, also this. My infantry gun company is talking taking it easy in this village Szlachecka. We occupy twelve medium-sized farms, with farmhouses and barns and fields, looking like peacetime. The war has passed our village by. Those are the good things about it. Admittedly, this is no German village. It is dirty everywhere, tight and inhospitable. But for us it is a resting place, quarters for man and horse, gun and tractor. My man Kuhlhüser said the night we got here: “Lieutenant, the dogs are barking, there are still people here, nothing is broken. Here, we can make ourselves at home!” Kuhlhüser, a staid Westphalian, has an eye for practicalities. He has a special sense for decisively emphasizing the best aspects of things. Gefreiter Kuhlhüser fits in life and really fits in the field. And he was right here also. We made ourselves as cozy as possible.

The first night, we slept like the horses in the straw barns. We sealed the cracks between the boards with bundles of straw. In this way we prevented a draft, but we froze anyway. It was a cold night on one of the last days of September. Because it was similar with the other companies and regiments, and so many still had diarrhea from the advance. the division gave the order: Out of the barns, into the houses! Warm up!

We moved in to the living room of the farm house, seventeen men strong. My lads moved the few furniture items belonging to the old horse farmers who lived alone on the farm, their two sons having been called up for Poland, into the side room. We laid straw on the floor of the living room, and there we slept, me with my company staff and a few men. We sit and lie on the straw and write on the folding steel desk, which we hadn’t set up in a tent even once. This is all lovely for us, we eat, drink, sleep, read, write, tell stories. Schütze Franken, a jolly Rhinelander, plays harmonica. He is a master at it.

And this morning, my men brought me something: a Polish typewriter. They had gone into a desolate country town to buy tobacco. But there was not a single Pole there, and the German comrades quartered there also had nothing to smoke. There, the boys had found the Polish typewriter in the yard of a half shot out and burned out house, and they had taken it with them. They arrived beaming: Maybe I could get good use of this? It was not exactly new, it was also partially in pieces, and very dirty. But the armorer would soon take care of that.

The armorer tinkered with it, and soon he too was beaming, glad to have succeeded with this peaceful task. Now it works, now it writes! I should try it out, and maybe I should try it out a little more, he urged gently. He was really curious to see if his repairs to the machine had fixed it.

Thus, I started with a couple of letters, and a couple of words, and a sentence, written on the machine. It typed and clacked and occasionally rang, light and fine. The men of my staff heard this, crawled out of the straw and looked over the shoulders of the armorer and me. A miracle in war: a typewriter at work, in the middle of a war! Had such a thing ever happened?

The typewriter is practical. Only for the lower and upper case “L” must I use the Polish letters, with a short diagonal line through the vertical stroke. That is Polish, and the Polish typewriter can’t take offense to that.

We entertained ourselves for a long time with the typewriter. A few wanted to learn to type, even here. For now, sure. But the main thing, we all decided in a comradely way, was for me to sit down and write what we had experienced, in the campaign in Poland.”