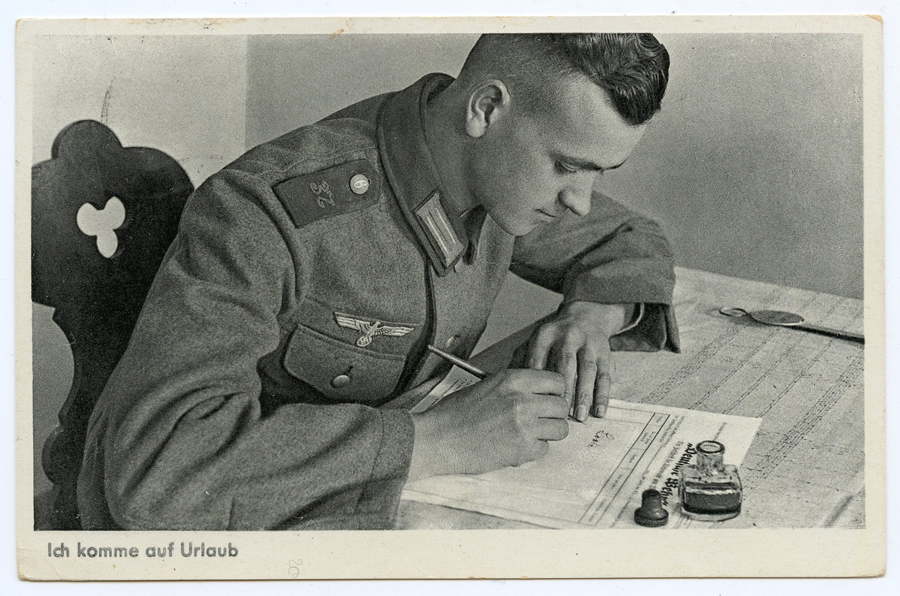

The two main types of pens used by German clerks and officials in WWII were fountain pens and dip pens. Fountain pens, which had internal reservoirs for ink, were rather expensive, and often personal for the owner. Dip pens, which needed to be dipped in ink to write, were the common disposable permanent writing instrument. This 1930s postcard shows a dip pen in use.

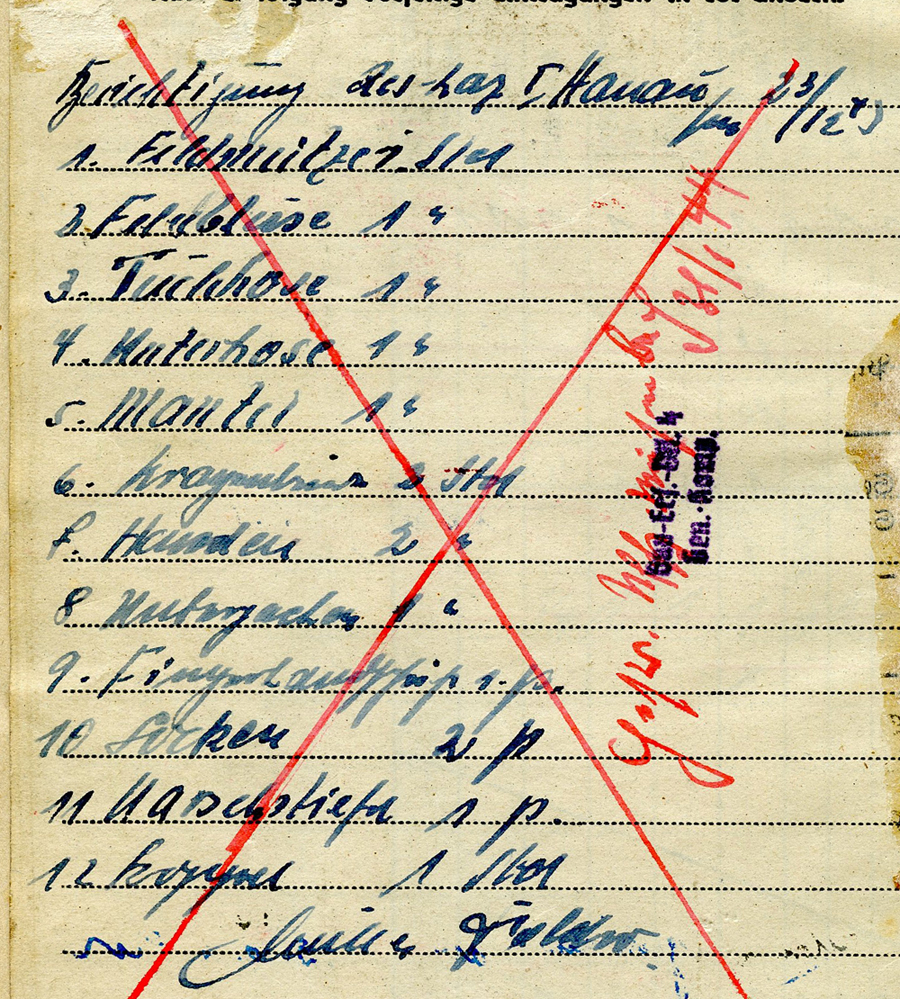

It’s likely that an officer or clerk would have had a fountain pen, but if that pen were lost or damaged, a dip pen might have been the only pen available. It’s also possible that some people chose to use cheap dip pens for their work, because they preferred it or because it’s what they were used to. Early gold dip pen nibs, which were out of fashion by the 1940s, lasted almost forever; the 1940s dip pen nibs were steel and were mostly only intended to last for a while before being replaced, though some types probably would write perfectly well for an indefinite period of time. In most cases, looking at a brief Soldbuch entry, it’s impossible to determine if a dip pen or a fountain pen was used. Here is a longer entry, that was definitely written with a dip pen. You can see that the author paused to dip his pen in the middle of the word “Socken,” item 10.

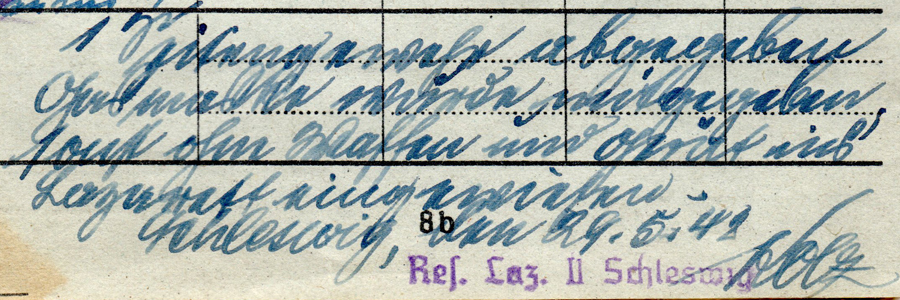

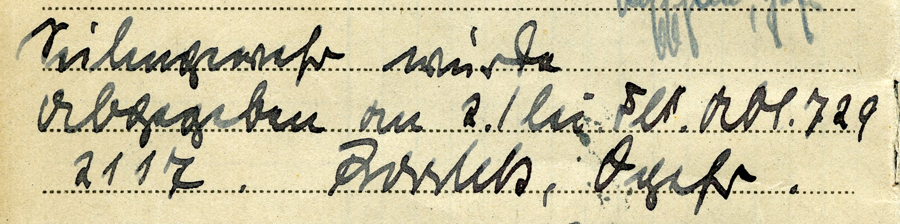

This entry was likely also written with a dip pen, based on the uneven look. Fountain pens generally deposit ink evenly as a person writes.

The part of the pen that touches the paper, is the nib. Before the war, it was normal for fountain pens to have gold nibs, with gold-plated or simple steel nibs being used for cheap pens such as “school pens” used by some students. During the war, materials shortages necessitated the use of steel for nibs on even high end pens.

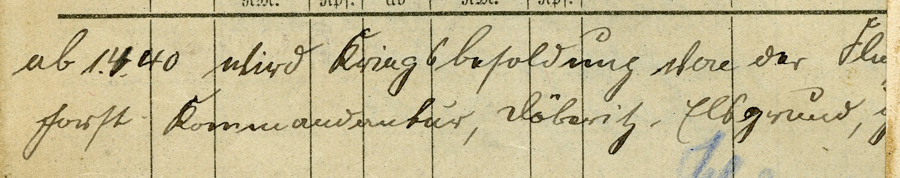

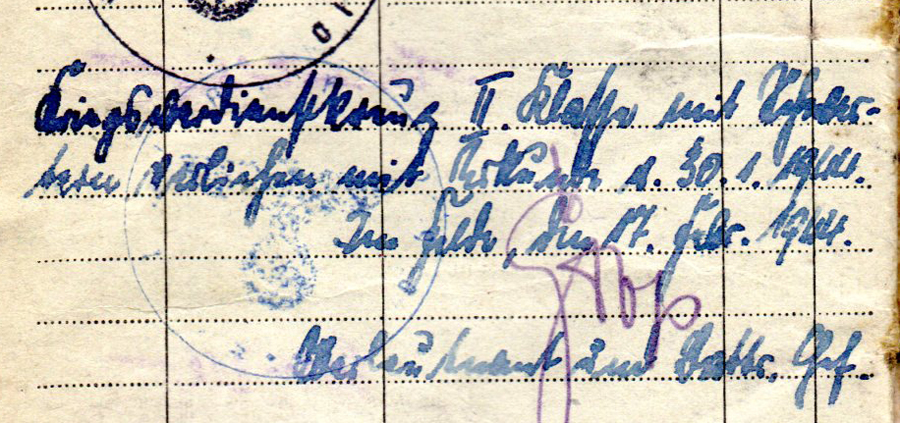

Both dip pens and fountain pens existed with a tremendous variety of nibs. Many of the nibs made and used in those years were flexible and would write a line that could vary in thickness, depending on the pressure applied by the writer. With this type of nib, it was normal for the writer to use more pressure on down strokes, less on up strokes, so the down strokes were thicker lines. Here are some examples of entries made with flexible nibs.

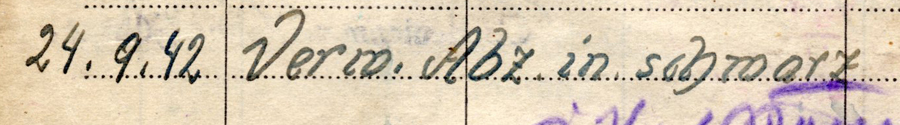

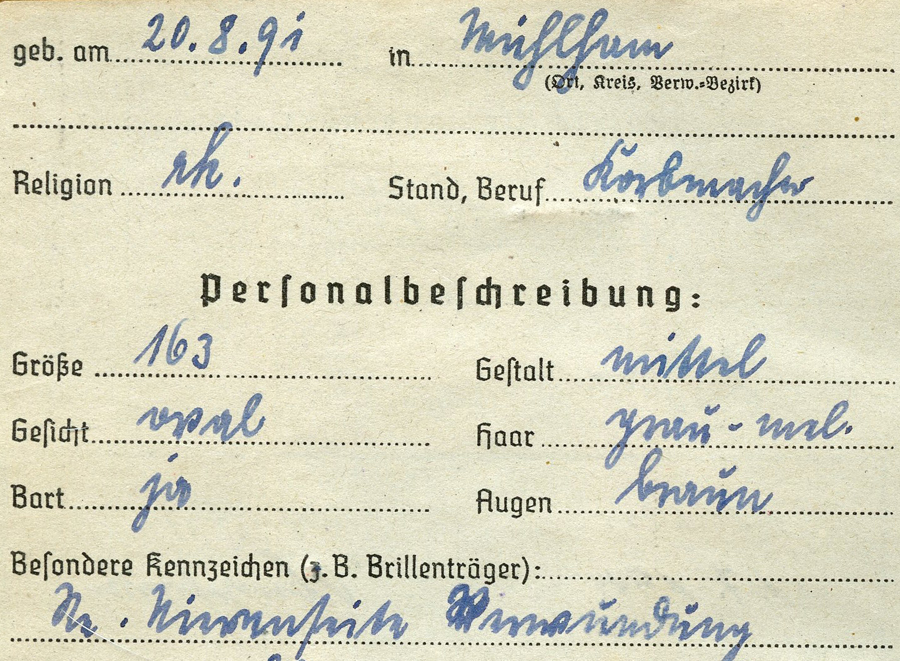

There were also “italic” or “stub” nibs, that created line variation not by being flexible, but simply as a result of the angle with which they were held. Looking at handwriting that shows line variation, it can be hard to tell if it is the result of a flexible pointed nib, or an italic nib. This entry, with its subtle but very consistent line variation, may have been written with an oblique nib such as a “LY” dip pen nib from Heintze & Blanckertz.

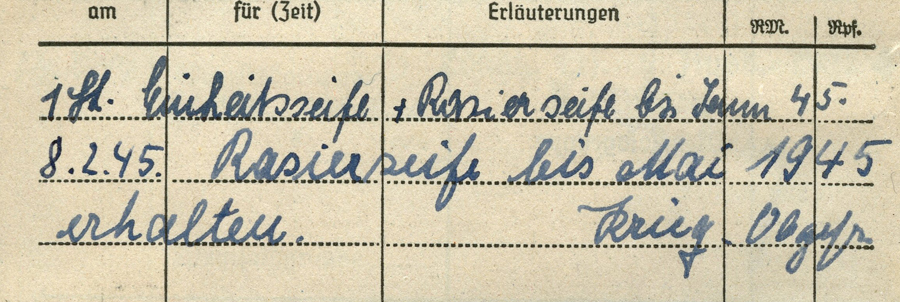

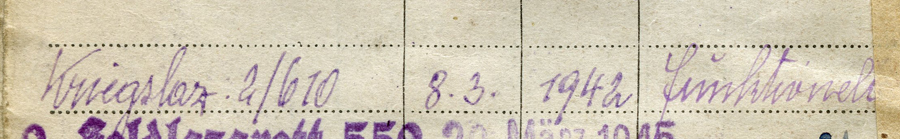

Not all period nibs offered line variation. Fountain pens and dip pens were also available with inflexible nibs, intended for “monoline” script styles in which the width of the written line remains constant. Sütterlin was intended to be written with such a nib. A wartime and prewar style of dip pen nib that wrote this way was the “Redis” nib by Heintze & Blanckertz. Here are some wartime examples of writing with monoline nibs.

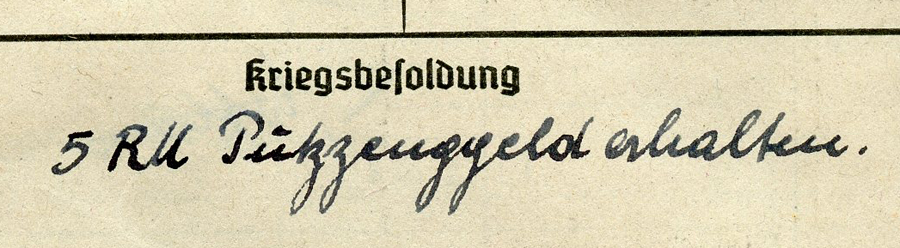

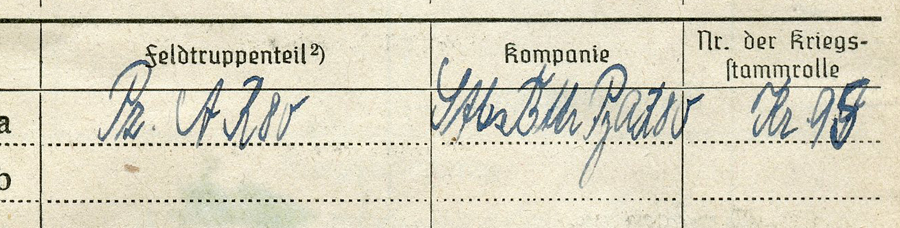

Many Soldbuch entries were made by pens that had very fine nibs. Such nibs were well-suited for the very small writing required for some Soldbuch work.

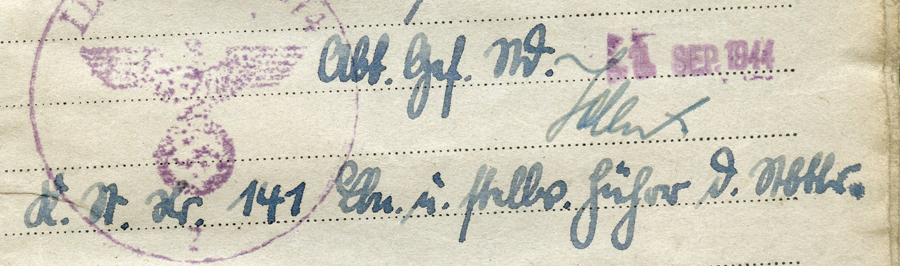

But not all clerks or officials used pens with fine or extra fine nibs.

Recreating historical writing does not absolutely require using historical tools. Modern fountain pens and dip pen nibs still write the same way. To fill out a Soldbuch, it is good to have a variety of inks and nibs to recreate the appearance of entries made by different people at different times. It is ideal to have a mix of flexible (or italic) and monoline nibs, and some of those nibs should be fine or extra fine. Calligraphy nibs that are broader than 1.1 mm were generally not used for the type of everyday script found in the Soldbuch.

I use dip and fountain pens every time I want to practice writing in period script. You can’t make realistic-looking period handwriting with a ballpoint pen.